What is your research project and why were you drawn to it?

What is your research project and why were you drawn to it?

I work in the James Russell Lab studying paleoclimate with a focus on reconstructing the terrestrial paleoclimate of the Congo River Basin during the mid-pleistocene transition (my record spans 1.2 million to 700,000 years ago) using marine sediments deposited off the Congo River fan. This involves drilling sediment cores that extend millions of years back in time and analyzing the organic compounds they contain, which serve as proxies for temperature, hydrology, and wildfire frequency.

I was drawn to this area of research because I’m passionate about chemistry and the environment, especially when it comes to combating climate change. Though paleoclimate research may appear to be isolated from understanding modern climate change, creating a reliable and thorough record of past climate patterns is crucial for predicting future climate behavior. Take my thesis project for example: I am studying how much warmer and drier the Congo River Basin was before the mid-pleistocene transition, which brought on sustained cooling trends across the globe. Right now, the Congo is the driest rainforest in the world; some fear that with continued warming, it may collapse into savannah and release large amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere through fires and the outgassing of peat. I’m hoping my research can help us understand the climate threshold at which the Congo rainforest can sustain itself, or, in other words, how much heat and drought it can withstand. It’s through projects like this that paleoclimate scientists can help predict the effects of climate change on localized regions and communities.

What is the most surprising thing you’ve learned?

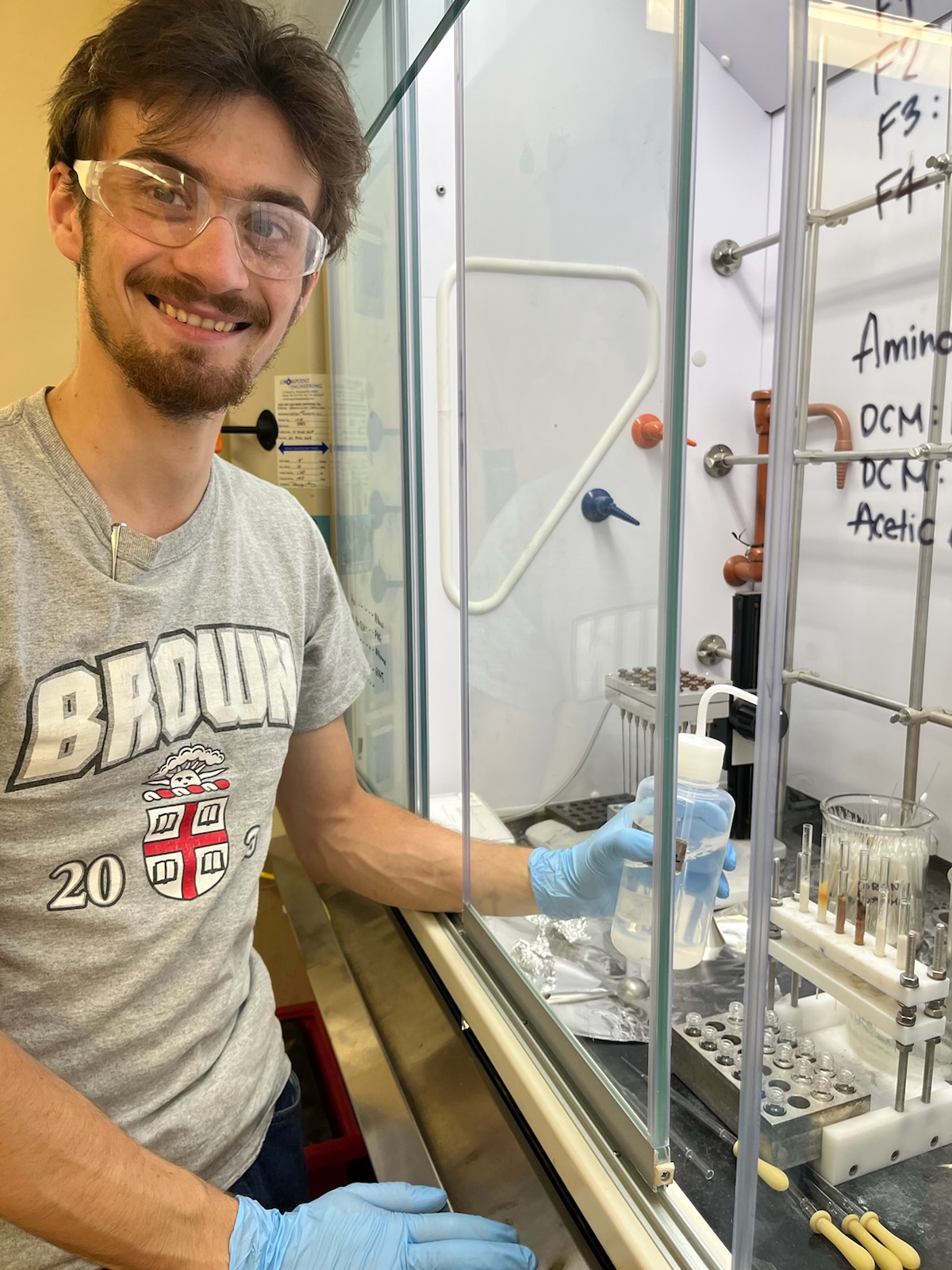

I’ve always marveled at the ability of paleoclimate research to accurately reconstruct the average temperature in a given region from millions of years ago; the idea that the rocks we tread on underfoot (or swim over in lakes) are rich with information and offer us the ability to understand what it used to be like on Earth is beautiful. I often think about it as piecing together a puzzle: lab work can be very abstract—you’re grinding up sediments, running them through solvents to extract the organic compounds, running them on instruments to get this data—but the end result is a tangible story that connects back to the real world, and paints an increasingly clear picture of the history of our planet.

Why DEEPS?

As a scientifically-minded person, I’ve approached my passion for protecting the environment through a geochemical lens. Though I initially thought I would concentrate in environmental science, it was important to me that I understand the hard science behind climate change. DEEPS offered just that, as well as a welcoming, supportive community and a pathway to research opportunities in Jim’s lab that have allowed me to contribute to important work as an undergraduate and prepared me to go out into the world and confront climate change.

---

The Student Research Stories are a new series of interviews showcasing the research journeys of undergraduate students in the Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Science (DEEPS). The series is organized and created by DEEPS Communications Assistants Hania Khan and Isabel Tribe.